Welcome to the Poppy Field

Superbloom is coming. On January 28.

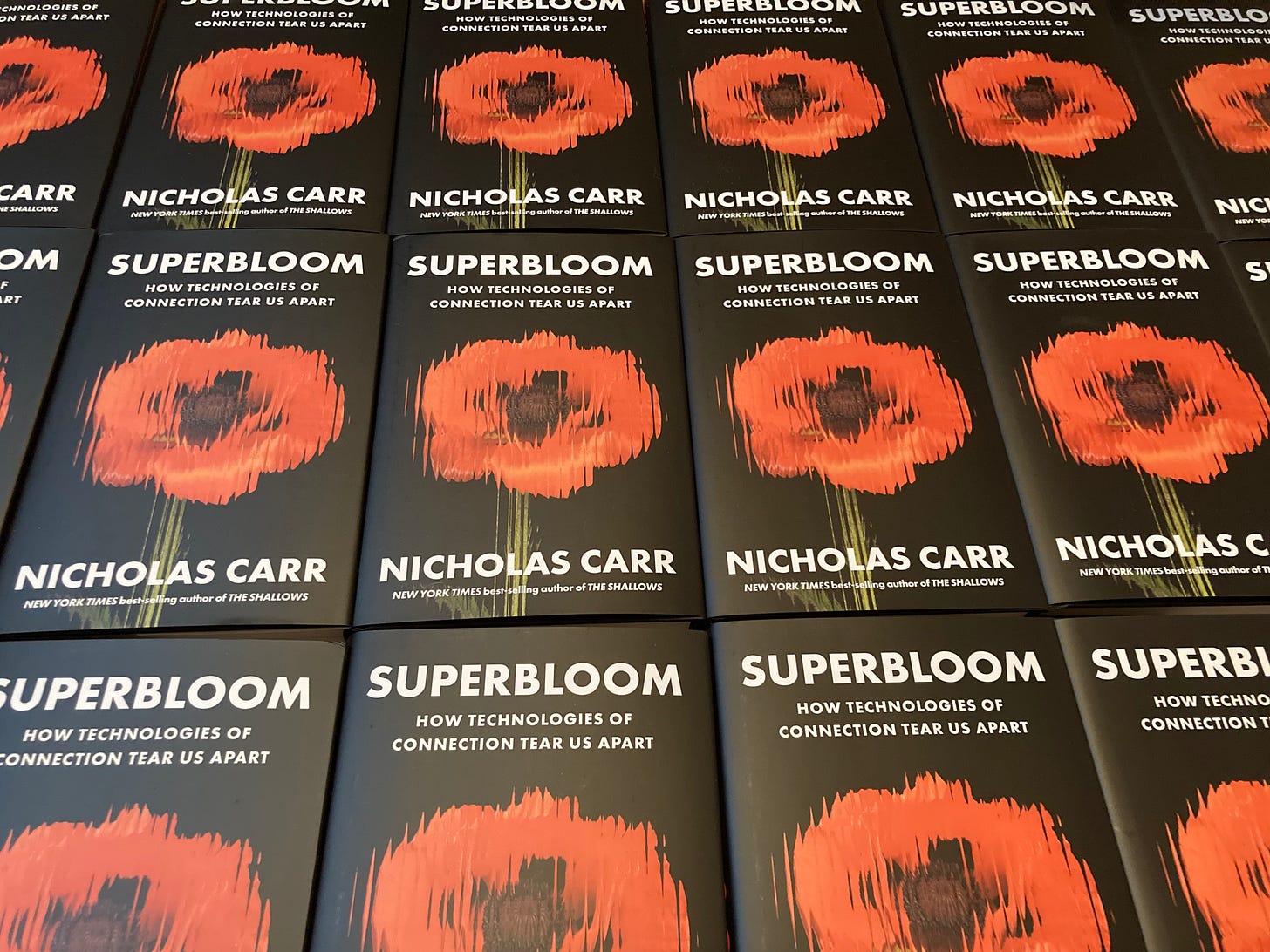

My new book, Superbloom: How Technologies of Connection Tear Us Apart, doesn’t come out until the end of January, but I just received my box of author copies. I will spare you the unboxing video (though it is exceptionally engaging), but I won’t spare you the photo:

Superbloom offers a cultural history of communication, particularly in its mechanized, mediated form, that culminates in an exploration of how one particular media machine, the computer network, shapes the way we communicate today — what we say, how we say it, whom we say it to. (Read an excerpt.)

Because a society is formed and sustained through acts of communication, the story of communication technology is also necessarily a story of social change. One of the book’s epigraphs comes from the early-twentieth-century American sociologist Charles Horton Cooley:

And when we come to the modern era, especially, we can understand nothing rightly unless we perceive the manner in which the revolution in communication has made a new world for us.

Cooley, who was born in 1864 and died in 1929, lived during the first stage of what might be called the electrification of communication. With the advent of telegraphy, telephony, and broadcasting, messages and other information could suddenly move faster than human beings themselves could move. Before telecommunication, information was cargo (letters, newspapers, books, catalogs), and communication systems were transportation systems. After telecommunication, information lost its material form, and media empires like Western Union and AT&T, RCA and NBC, arose to take control of its instantaneous transmission.

But communication still took place on a human scale during that time. The constraints and frictions of analog transmission limited the speed and volume of information flows and encouraged discipline and discretion in people’s reading, viewing, and listening habits.

That all changed when the computer network entered the home at the close of the last century. We soon came to see the constraints and frictions of analog communication as problems — problems that digitization could solve. It’s only with the vast project of media digitization in our own time that human communication has lost its human scale. As the French philosopher Jean Baudrillard dryly observed in 1995, at the dawn of the digitization project, “Words move quicker than meaning.” What happens to us when words, as well as images, conversations, and all other forms of information, move quicker than meaning is Superbloom’s subject.

As I was writing the book, I came to see the thematic thread that ties it together with my two previous books, The Shallows and The Glass Cage. The three works examine how we came to apply industrial ideals and measurements — efficiency, productivity, speed, profit — to the most essential and defining of human pursuits. The Shallows looks at the application of those ideals and measurements to thinking; The Glass Cage, to doing; and Superbloom, to communicating. The way computer systems have abetted the encroachment of the industrial ethos into the most intimate facets of human life strikes me as one of the most important stories of our time.

And, yes, Superbloom’s subtitle is an allusion to the Joy Division song.

Pre-ordered! I can still remember how eye-opening (and frankly life-changing) The Shallows and The Glass Cage were when I first read them almost a decade ago. Happy to support your work and looking forward to reading the latest.

Congratulations! This will be the first book on my reading list for next year:) I read "The Shallows" over a decade ago and felt encouraged to find such incisive writing on the perils of technology. Looking forward to sharing this with my readers as well!