Truth Doesn't Scale

Why online fact-checking will never work.

I’ve been fact-checked. It’s an uncomfortable experience but also therapeutic. One has one’s flaws exposed — sloppiness, overreaching, wrong-headedness, impetuousness, ignorance, peevishness — and dealt with. Nothing gets swept under the rug; it all has to be resolved on the page, in public view. One emerges from a rigorous fact checking a chastened, and maybe a better, writer and man. And one avoids the embarrassment of the printed error, the unerasable kind. Fact checkers are an irritant. I salute them.

Sometimes fact checking is, like a Joe Friday interrogation, strictly about the facts. You get a date wrong. You garble a quotation. Usually, though, it’s fuzzier. It’s about interpretation. Are you pushing the facts too far? Are you skewing the evidence? Are you drawing a clear enough line between opinion and fact? In summarizing some event or concept, are you distorting it? There are no clear-cut answers to such questions. It comes down to a negotiation among writer and checker and editor, each of whom, like everyone else on the planet, has imperfect judgment. The negotiation is less about establishing a point of truth than about establishing truth’s boundaries.

Mark Zuckerberg is a silly man. (I sense that with his recent James Caan Action Figure makeover, he has achieved peak silliness, but I don’t want to underestimate him. He could still surprise me.) But his decision to end Meta’s outsourced fact-checking program was the correct one, if only because it ended a pantomime. And the timing of the announcement, on the the eve of the Trump restoration, was fortuitous in its cynicism, as it made clear that the Meta program was always about politics, not epistemology. Meta’s third-party fact checkers weren’t mapping the boundaries of truth. They were mapping the boundaries of orthodoxy.

Zuckerberg’s decision to follow the lead of that intrepid and omnipresent truth-seeker, Elon Musk, and set up an X-like system of “Community Notes” is another political act, of equal cynicism. Handing off authority for fact checking to “the community” has practical advantages for Meta, as it did for X. The community doesn’t send invoices. Fact checking, like content creation, is unpaid labor that users, or at least some small subset of them, will contribute for free. And by “democratizing” fact checking, Meta gains a buffer against criticism. Responsibility, and blame, is shifted onto a faceless public.

Power to the people? Not quite. With Community Notes, the algorithm, as always, gets the final say. A volunteer fact checker proposes a note to attach to some dubious or simply contentious post. Other volunteers vote on whether the note should be published. And then the Meta algorithm steps in, weighs the votes according to its assessment of each voter’s viewpoint and objectivity, and makes a go/no go decision. The negotiation takes place within a black box. Democracy is a ghost in the machine. And by the time a decision is rendered — hours or days after the fact — the disputed post has circled the globe a thousand times.

Fact checking works, if imperfectly, in traditional publishing because it’s conducted by a small set of people who share similar values and goals. They may have different views about any number of matters, but they hold a common belief in the standards of journalism, a belief that the accuracy of information is a public good. Even if you’ll never arrive at capital-t Truth, the ideal of Truth gives you a useful set of bearings. It leads you to the best possible decision, in advance of publication.

Take fact checking out of that intimate, human setting, turn it into an industrial program of outsourcing, crowdsourcing, or automation, and it falls apart. It becomes a parody of itself. The desire to “scale” fact checking, to mechanize the arbitration of truth, is just another example of the tragic misunderstanding that lies at the core of Silicon Valley’s entire, grandiose attempt to remake society in its own image: that human relations get better as they get more efficient. A community, we seem fated to learn over and over again, is not a network.

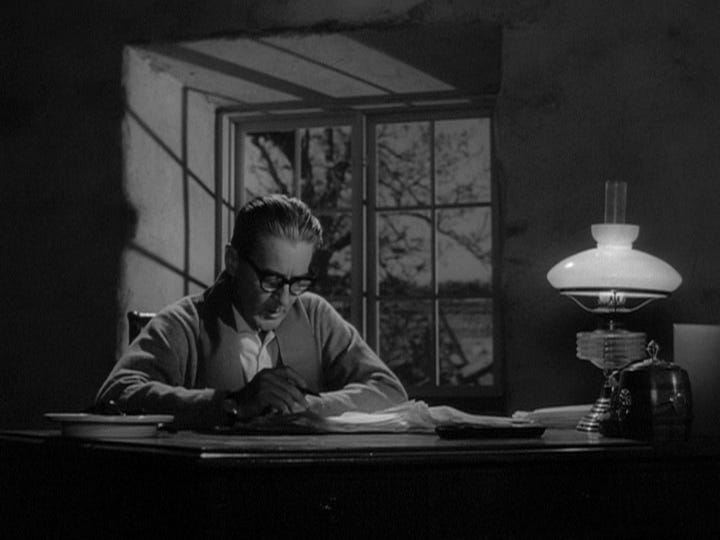

I agree with these considerations. However, all things considered, my impression is that X's community notes system appears to be working more effectively. This is just my personal observation though, as I don't have data to support this claim. In that sense, you could say my opinion is like the photo on a freeze-dried meal package: it looks appealing (to me) but might not perfectly represent reality.