The Erasive Age

Generation as destruction.

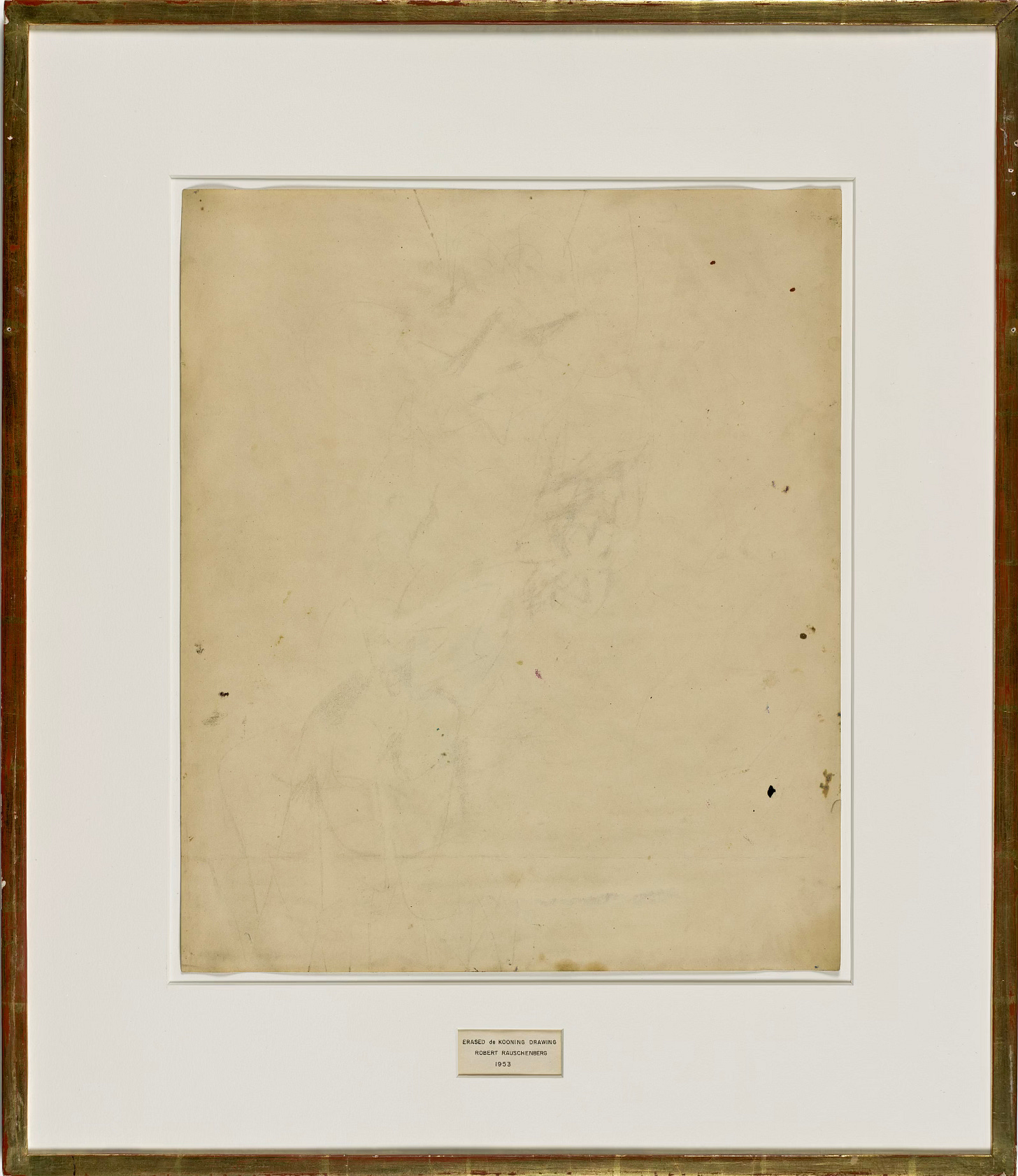

One day in 1953, a young and at the time little-known experimental artist named Robert Rauschenberg arrived at the studio of the great abstract expressionist Willem de Kooning bearing a bottle of Jack Daniels and a strange request. He wanted the famous artist to give him one of his drawings so he could erase

it. De Kooning was taken aback. “I remember that the idea of destruction kept coming into the conversation,” Rauschenberg later recalled, “and I kept trying to show that it wouldn’t be destruction.”

Rauschenberg explained to de Kooning that he wanted to see if a work of art could be created not just through the inscription of marks but through their removal. Could art be erasive as well as inscriptive? After much back-and-forth, and several servings of brown liquor, de Kooning agreed to the request. He chose a drawing he had recently completed — one he was fond of — and gave it to Rauschenberg.

Over the course of the next two months, Rauschenberg slowly, meticulously erased the drawing, taking off layers of grease pencil, charcoal, graphite, and ink. He went through forty erasers. All that remained in the end were a few faint traces of the original sketch. With the help of his friend Jasper Johns, he then carefully matted and framed the work, and Johns wrote a label for it, inscribing the title, artist, and date so precisely that they appeared to have been printed out by a machine:

ERASED de KOONING DRAWING

ROBERT RAUSCHENBERG

1953

“The simple, gilded frame and understated inscription are integral parts of the finished artwork,” writes a curator at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, which acquired the work in 1998, “offering the sole indication of the psychologically loaded act central to its creation.” Even a work of erasure demands a frame, Rauschenberg understood, a boundary establishing its place in the world. Erasure cries out for inscription. We want to know the marks were there before they weren’t.

Erasive is an exceptionally uncommon word. It was coined in the seventeenth century but has rarely been used since. Word-processing and messaging spellcheckers underline it with suspicion. Its rarity testifies to our discomfort with, as the SFMOMA writer terms it, the “psychologically loaded act” of erasure. But, thanks to the rise of what tech companies have cheerfully branded “generative AI,” the word seems certain to be used more often in the years to come. Our condition demands it. Behind every act of AI generation lie many acts of erasure. We have entered the erasive age.

Although we assume that media is fundamentally inscriptive, a means of preserving and transmitting human-made marks of one sort or another, communication systems have always also entailed erasure. What they erase are the spatiotemporal boundaries that in nature fix speech to speaker. A person says something, and if there are others in earshot, they hear it. Otherwise it’s gone. But that same person writes those same words down on a sheet of paper, or enters them into a computer network, and the words can travel through space and persist through time. Much of the value of media, cultural and financial, has always stemmed from its power to erase the material world’s physical constraints on the flow of speech, the flow of information.

So long as erasure served our desire to transmit our own marks and receive the marks made by others, we didn’t worry about it. We celebrated it — the death of distance! the transcendence of time! — just as we celebrate other technologies that free us, or at least shield us, from the world’s frictions and constraints. We want our marks, and the marks of others, to flow freely through space and time. We want the speech of distant people to arrive in our mailbox, to issue forth from our radio and TV, to hang on the walls of a museum, to appear on the screen of our phone. Take away such freedom of movement, return us to the original communication system of mouth and ear, and you take away knowledge, culture, science, entertainment, pretty much the entirety of modernity.

Erasure is good for business. The more of the world that media erases, the more dependent society becomes on the systems and services of media companies and the more profits those companies earn. That’s why people like Mark Zuckerberg have been so eager to promote the benefits of “frictionlessness” in communication and social relations. What we failed to appreciate is that the pursuit of profit would lead the companies beyond the erasure of spatiotemporal boundaries. They would seek to erase the greatest source of friction in their operations: their reliance on human creativity and expression. They would seek to replace the human source of the information they transmit — speakers and their speech — with highly efficient machines capable of creating “content” cheaply and on demand.

In creating tradable derivatives of human speech, AI erases the human voice, the human hand. First, it turns the works of culture into numbers, then it compresses those numbers into a generalized statistical model. Of the originals only traces remain. If Rauschenberg sought to show that erasure can be a generative act, AI bots have the opposite goal: to show that generation can be an erasive act. Fulfilling de Kooning’s fears, generation turns destructive.

It’s useful to bring in another work of art, Vilhelm Hammershøi’s 1913 oil painting Interior with Windsor Chair:

As the art critic Shawn Grenier has explained, the chair in the painting, like the faint traces of the original de Kooning drawing in Rauschenberg’s work, has the paradoxical effect of accentuating the painting’s air of emptiness. In both works, we sense not only an absence but also the presence — the human presence — that preceded the absence. It’s that same memory of human presence that, to the discerning mind, gives the products of generative AI their poignancy.

The more we draw on AI to shape our perception and understanding of the world, to structure our thoughts and words, to express ourselves, the more complicit we become in erasing culture, the past, others, ourselves. Eventually, should we continue down the path, even the memory of what’s been erased will be erased. No frame, no matting, no inscription. Only the empty revelation of erasure.

This post is an installment in Dead Speech, a New Cartographies series about the cultural and economic consequences of AI. The series began here.

The essay you provided is a beautiful piece of melancholy prose, but it rests entirely on a Category Error. It confuses abstraction with destruction. The author is mourning the "erasure" of the human hand, but they are looking at a library and calling it a bonfire.

The text opens with the story of Rauschenberg erasing a de Kooning drawing. This is a powerful metaphor, but it is physically false when applied to AI. Rauschenberg physically destroyed a unique object to create art. AI does the same to culture, turning "works into numbers" until "only traces remain." When Rauschenberg erased the drawing, the drawing was gone. When an AI trains on a painting, the painting remains untouched. The original De Kooning hangs in a gallery; the JPEG sits on a server.

AI is not "erasing" culture; it is reading it. It is the most voracious reader in history. It does not destroy the text; it memorizes the patterns of the text. To call learning "erasure" is to argue that a student destroys a textbook by reading it and understanding the concepts within. We are not entering an "Erasive Age"; we are entering the Archival Age, where the sum total of human creativity is preserved in a functional, living matrix. Digitization is not Destruction.

The author argues that tech companies are removing the "friction" of human creativity (the actual labor of painting/writing) and that this is a tragedy.

The "friction" (the difficulty of execution) is where the humanity lives. By removing it, we erase the human. This is the "Sweat Equity" fallacy. It assumes that art is valuable only because it was hard to make.

Did the camera "erase" the humanity of the portrait painter?

Did the synthesizer "erase" the humanity of the violinist?

AI removes the technical friction (barrier to entry), not the creative friction (the idea). By making execution "frictionless," AI democratizes expression. It allows a paralyzed person to paint, or a tone-deaf person to compose. It doesn’t erase the human; it amplifies the human intent, freeing it from the constraints of manual dexterity.

The text laments that AI "turns works of culture into numbers... compressed into a statistical model." Reducing art to math kills the soul of the art. This is essentially Digital Vitalism—the belief that "numbers" are cold and dead, while "ink" is warm and alive.

Everything is information. A vinyl record turns a voice into physical grooves. A book turns thoughts into ink splotches. A JPEG turns a painting into binary. The "statistical model" is just a high-dimensional map of human meaning. It is not a reduction; it is a synthesis. It connects the style of Van Gogh to the style of Monet and finds the mathematical relationship between them. That isn't destruction; that is profound, mathematical understanding.

The author uses the Hammershøi painting (the empty chair) to argue that AI art feels empty because we sense the absence of the human who should be there. AI art is "poignant" only because it reminds us of the human that isn't there. This assumes the AI is acting alone. It ignores the Prompter. The "human presence" in AI art is the User. When you prompt an AI, you are the director. The AI is the brush. The author is mourning the lack of a "painter" while ignoring the presence of the "architect." We don't look at a cathedral and say, "This is empty because the architect didn't lay every brick with their own hands." We admire the vision. AI shifts art from manual labor to conceptual vision.

The text concludes with a dystopian fear: "Even the memory of what’s been erased will be erased." This is pure Luddite projection. Claim: AI grinds culture into a grey goo of content.

To the contrary , AI is a prism. It takes the white light of total human culture and allows us to refract it into new, infinite colors.

We aren't erasing de Kooning. We are giving every human being on Earth the ability to collaborate with de Kooning, to converse with Shakespeare, and to jam with Hendrix. It is the ultimate inscription—writing humanity so deeply into the machine that our creativity becomes a fundamental principle of its physics.

Though I share concerns about AI, the metaphor of erasure is stretched. First, communications technology does not “erase” boundaries. It shatters them. Breaks through them. Unlike erasure, this leaves no trace of the original boundary.

Next, while any AI response can certainly replace a human response, it can also steer us towards human creations, weeding through the vast clutter of art, literature, etc to recommend a work which has not, therefore, been erased but highlighted. And unlike deKooning’s erased work, the original is still there for our enjoyment. Those who use AI an an end, to write papers or answer questions that they have no intention of exploring further, are guilty of erasing a human voice or job. But those who use AI as a portal to further research and exploration are doing the opposite of erasure. They are expanding horizons.