The Arc of Innovation Bends toward Decadence

Why our inventions seem so small.

For years, people have bemoaned the sorry state of innovation. Compared with the great inventions of the industrial era, the inventions of our own time seem pathetic. In today’s Sunday Rerun, I offer a different take: We’re as innovative as ever, but the focus of innovation has shifted. The post originally appeared in 2012.

“If you could choose only one of the following two inventions, indoor plumbing or the Internet, which would you choose?” –Robert J. Gordon

The Harvard Business Review’s Justin Fox is the latest pundit to ring the innovation-ain’t-what-it-used-to-be alarm. “Compared with the staggering changes in everyday life in the first half of the 20th century,” he writes, summing up the by now familiar argument, “the digital age has brought relatively minor alterations to how we live.” Fox has a lot of company. He points to science-fiction author Neal Stephenson, who worries that the Internet, far from spurring a great burst of creativity, may have actually put innovation “on hold for a generation.” Fox also cites economist Tyler Cowen, who has argued that, recent techno-enthusiasm aside, we’re living in a time of innovation stagnation.

He could also have mentioned tech powerbroker Peter Thiel, who believes that large-scale innovation has gone dormant and that we’ve entered a technological “desert.” Thiel blames the hippies:

Men reached the moon in July 1969, and Woodstock began three weeks later. With the benefit of hindsight, we can see that this was when the hippies took over the country, and when the true cultural war over Progress was lost.

The original inspiration for such grousing — about progress, not hippies — came from Robert J. Gordon, a Northwestern University economist. His influential 2000 paper “Does the ‘New Economy’ Measure Up to the Great Inventions of the Past?” included a damning comparison of the flood of inventions of a century ago with the seeming trickle we see today. Consider the products invented in just the ten years between 1876 and 1886: the internal combustion engine, the electric lightbulb, the electric transformer, the steam turbine, the electric railroad, the automobile, the telephone, the movie camera, the phonograph, the linotype machine, the film roll for cameras, the dictaphone, the cash register, vaccines, reinforced concrete, the flush toilet. The typewriter had arrived a few years earlier, and the punch-card tabulator, the computer’s precursor, would appear a few years later. And then, in short order, came the airplane, the radio, air conditioning, the vacuum tube, jet aircraft, the television, the refrigerator, and a raft of other home appliances, as well as revolutionary advances in manufacturing processes. (And let’s not forget The Bomb.)

The conditions of life changed utterly between 1890 and 1950, observed Gordon. Between 1950 and today? Not so much.

So why is innovation less impressive today? Maybe Thiel is right, and it’s the fault of hippies and other degenerates. Or maybe it’s crappy education. Or a lack of corporate investment in research. Or short-sighted venture capitalists. Or monopolistic business practices. Or overaggressive lawyers. Or imagination-challenged entrepreneurs. Or maybe it’s a catastrophic loss of mojo. None of these explanations makes much sense. The aperture of science grows ever wider, after all, even as the commercial and reputational rewards for innovation grow ever larger and the ability to share ideas grows ever stronger. Any barrier to innovation should be swept away by such forces.

Let me float an alternative explanation: There has been no decline in innovation; there has just been a shift in its focus. We’re as creative as ever, but we’ve funneled our creativity into areas that produce smaller-scale, less far-reaching, less visible breakthroughs. And we’ve done that for entirely rational reasons. We’re getting precisely the kind of innovation we desire — and deserve.

My idea is that there’s a hierarchy of innovation that runs in parallel with Abraham Maslow’s famous hierarchy of needs. Maslow argued that human needs progress through five stages, with each new stage requiring the fulfillment of lower-level, or more basic, needs. So first we have to meet our most primitive Physiological needs, and that frees us to focus on our needs for Safety, and once our needs for Safety are met, we can attend to our needs for Belongingness, and then on to our needs for personal Esteem, and finally, at the peak of Maslow’s pyramid, to our needs for Self-Actualization.

If you look at Maslow’s hierarchy as an inflexible structure, with clear boundaries between its levels, it falls apart. Our needs are messy, and the boundaries between them are porous. A caveman probably pursued esteem and self-actualization, to some degree, just as we today spend time and effort fulfilling our physical needs. But if you look at the hierarchy as a map of human focus, then it makes sense — and seems to be borne out by history.

In short: The more comfortable you are, the more time you spend thinking about yourself.

If technological progress is shaped by human needs, as it surely is, then general shifts in needs would also bring shifts in the nature of innovation. The tools we invent would move through the hierarchy of needs, from tools that help safeguard our bodies or coordinate social groups on up to tools that allow us to modify our moods or express our individuality — from tools of survival to tools of the self. Here’s my crack at what the hierarchy of innovation looks like:

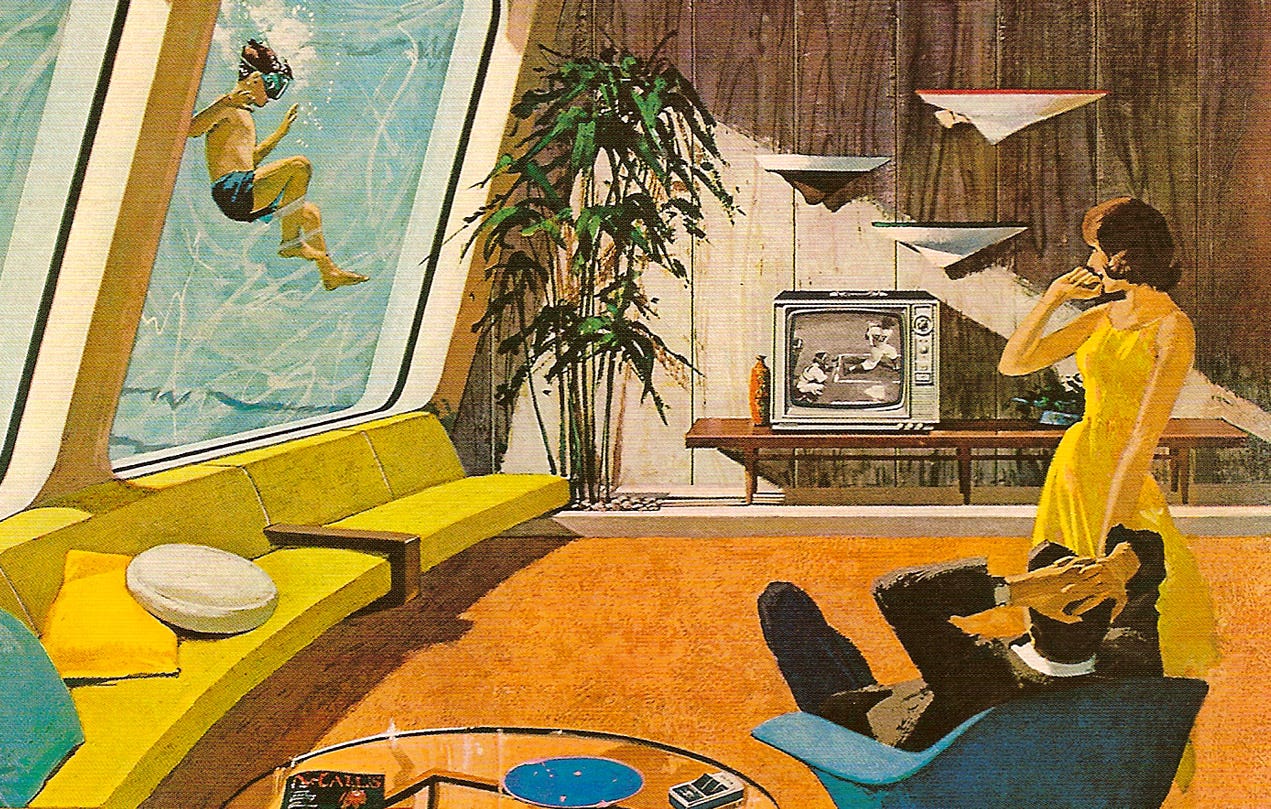

Innovation’s focus moves up through five stages, propelled by shifts in the needs we seek to fulfill. In the beginning come Technologies of Survival (think bow-and-arrow), then Technologies of Social Organization (think cathedral), then Technologies of Prosperity (think assembly line), then technologies of leisure (think TV), and finally Technologies of the Self (think Facebook, or Prozac).

As with Maslow’s hierarchy, you shouldn’t look at my hierarchy as a rigid one. Innovation today continues at all five levels. But the rewards, both monetary and reputational, are greatest at the top level (Technologies of the Self), which has the effect of shunting investment, attention, and activity in that direction. We’re already physically comfortable, so getting a little more physically comfortable doesn’t seem particularly pressing. We’ve become inward looking, and what we crave are more powerful tools for modifying our internal states or projecting those states outward to an audience. An entrepreneur today has a greater prospect of fame and riches if he or she creates a popular social-networking app than a faster, more efficient system for mass transit. Innovation, to put a dark spin on it, arcs toward decadence.

One of the consequences is that, as we move to the top level of the innovation pyramid, our inventions have less visible, less transformative effects. We’re no longer changing the shape of the physical world or even of society, as it manifests itself in the physical world. We’re altering internal states, transforming the invisible self. Not surprisingly, when you step back and take a broad view, it looks like stagnation — it looks like nothing is changing very much. That’s particularly true when you compare what’s happening today with what happened a hundred years ago, when our focus on Technologies of Prosperity was peaking and our focus on Technologies of Leisure was also rapidly increasing, bringing a highly visible transformation of the world.

If the current state of progress disappoints you, don’t blame innovation. Blame your own self-involved self.

Worth noting that this only applies to the median person. Plenty of people still struggling with the first few levels, even today.

I somehow missed this when you first published it in 2012. The idea of a Maslovian hierarchy of innovation strikes me as quite savvy, and in fact rather brilliant. Makes great sense. And it's certainly well illustrated by the transitional confluence of the 1969 moon landing and the advent of the Woodstock era that Thiel noted. Your mapping of innovation onto Maslow's pyramid of needs feels like it provides a new angle of illumination on the progress/decadence dynamic. Thank you for resharing it.