Strong Men and Strong Machines

Early warnings.

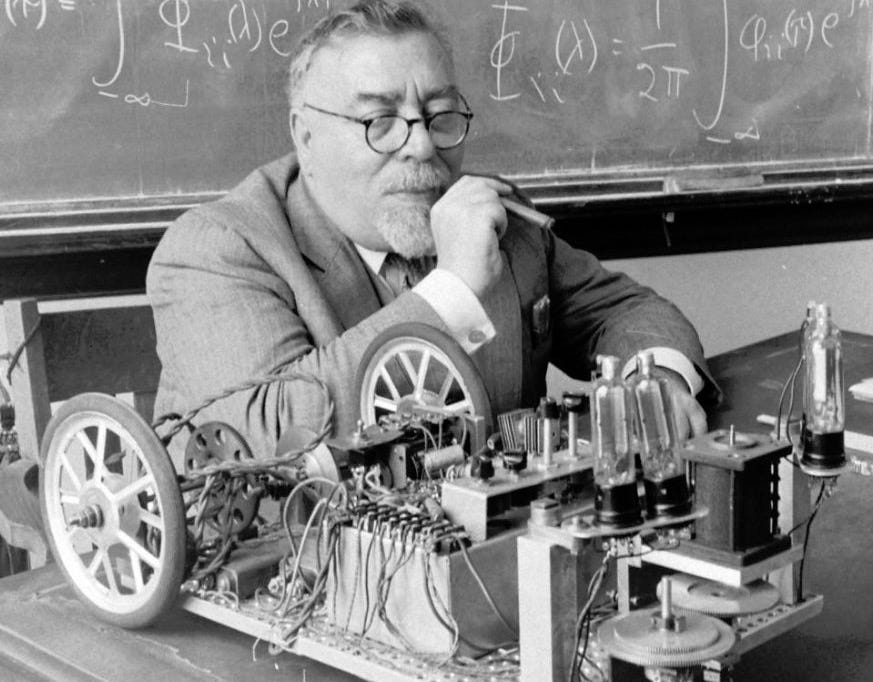

“The machines will do what we ask them to do and not what we ought to ask them to do.”

—Norbert Wiener

1.

In his 1950 book The Human Use of Human Beings, Norbert Wiener, the pioneering information theorist, tells the story of an early misreading of scientific evidence. After the invention of the microscope at the start of the seventeenth century, natural philosophers rushed to examine all kinds of substances with the new device. But one obvious candidate for such inspection — semen — they shied away from, fearful that such an interest might be deemed unseemly, if not depraved. Finally, in 1677, the intrepid Dutch scientist and inventor Antony van Leeuwenhoek placed a dab of his own ejaculate onto a slide and gave it a look. What he found, much to his amazement, was a swarm of wriggling little wormlike creatures, or “animalcules.”

Having discovered the male spermatozoon but not yet its much rarer female counterpart, the ovum, biologists of the time developed a theory of human reproduction, known as preformationism, that didn’t involve fertilization. The seed of a human life, it was thought, must be contained entirely in the bulbous head of the sperm. As Wiener explains:

The early microscopists were under the very natural temptation to regard the spermatozoon as the only important element in the development of the young, and to ignore entirely the possibility of the as yet unobserved phenomenon of fertilization. Furthermore, their imagination displayed to them in the front segment or head of the spermatozoon a minute foetus, rolled up with head forward.

The female of the species was merely the vessel, or, in Wiener’s term, the “nurse,” of the male-produced foetus. In the preformationist view, new life was created through the physical expression of what Mark Zuckerberg would much later call “masculine energy.”

2.

In the fall of 2005, the technology historian George Dyson, son of the renowned physicist Freeman Dyson, traveled to Google’s sprawling headquarters in Silicon Valley — the “Googleplex,” as everyone cheerily called it then. He had been invited to join a celebration marking the sixtieth anniversary of the publication of John von Neumann's “First Draft of a Report on the EDVAC,” in which the mathematician laid out the original design specifications for a digital computer.

Von Neumann wrote the paper in hopes of securing funding to build his proposed machine. The money rolled in. The main branches of the American military — Army, Navy, Air Force — offered their backing, anticipating all sorts of battlefield applications for a high-speed calculating machine. The biggest sponsor, though, was the recently established United States Atomic Energy Commission, which was taking over control of the facilities and machinery that had been used to produce the atomic bomb during World War II. The pact between von Neumann and the AEC was something of “a deal with the devil,” Dyson suggested in an essay, “Turing’s Cathedral,”1 written shortly after his Google visit, as the digital computer would turn out to be instrumental in the subsequent creation of the “super,” or hydrogen, bomb.

By breaking the distinction between numbers that mean things [i.e., data] and numbers that do things [i.e., executable instructions], von Neumann unleashed the power of the stored-program computer, and our universe would never be the same. It was no coincidence that the chain reaction of addresses and instructions within the core of the computer resembled a chain reaction within the core of an atomic bomb. The driving force behind the von Neumann project was the push to run large-scale Monte Carlo simulations of how the implosion of a sub-critical mass of fissionable material could lead the resulting critical assembly to explode.

“The actual explosion of digital computing,” Dyson commented, “has overshadowed the threatened explosion of the bombs.”

Later in his essay, Dyson described his visit to the Googleplex, an experience that had left him uneasy. “The mood was playful,” he wrote, “yet there was a palpable reverence in the air.” Dyson, who had long been fascinated by humankind’s desire to create an artificial intelligence, sensed that Google’s ambitions went far beyond “organizing the world's information and making it universally accessible and useful,” as its famous mission statement had it. The company had recently begun scanning millions of books into its data banks, and when Dyson asked a Google engineer about the effort, the engineer replied, “We are not scanning all those books to be read by people. We are scanning them to be read by an AI.”

The search engine was a front, a means of making an enormous amount of money and accumulating an enormous amount of data.2 What Google was really working on was the creation of an artificial intelligence. “It is 1945 all over again,” wrote Dyson.

When I [left the Googleplex], I found myself recollecting the words of Alan Turing, in his seminal paper “Computing Machinery and Intelligence,” a founding document in the quest for true AI. “In attempting to construct such machines we should not be irreverently usurping His power of creating souls, any more than we are in the procreation of children,” Turing had advised. “Rather we are, in either case, instruments of His will providing mansions for the souls that He creates.”

Google is Turing’s cathedral, awaiting its soul. We hope. In the words of an unusually perceptive friend: “When I was there, just before the IPO, I thought the coziness to be almost overwhelming. Happy Golden Retrievers running in slow motion through water sprinklers on the lawn. People waving and smiling, toys everywhere. I immediately suspected that unimaginable evil was happening somewhere in the dark corners. If the devil would come to earth, what place would be better to hide?”

I remember reading Dyson’s essay the day it appeared in the science newsletter Edge and being struck by it. It reinforced my own as yet inchoate sense of uneasiness about Silicon Valley’s ambitions. I quoted Dyson’s friend’s ominous description of the Googleplex in the “Church of Google” chapter of my 2010 book, The Shallows. But when I recently went back and reread the essay, what really hit me was the paragraph that came next, which I had forgotten about:

For 30 years I have been wondering, what indication of its existence might we expect from a true AI? Certainly not any explicit revelation, which might spark a movement to pull the plug. Anomalous accumulation or creation of wealth might be a sign, or an unquenchable thirst for raw information, storage space, and processing cycles, or a concerted attempt to secure an uninterrupted, autonomous power supply. But the real sign, I suspect, would be a circle of cheerful, contented, intellectually and physically well-nourished people surrounding the AI. There wouldn't be any need for True Believers, or the downloading of human brains or anything sinister like that: just a gradual, gentle, pervasive and mutually beneficial contact between us and a growing something else. This remains a non-testable hypothesis, for now.

Today, Dyson’s twenty-year-old hypothesis feels more like a prophecy. The signs he sensed would herald the arrival of an artificial intelligence — an anomalous accumulation of wealth, an unquenchable thirst for raw information, a concerted attempt to secure an uninterrupted power supply — are on full display today. The only thing missing from the list is “a sudden, intense interest in gaining and wielding political power.”

3.

Written shortly after the defeat of the Nazis, amid the post-war expansion of the Soviet Union, Wiener’s Human Use of Human Beings is a book of its time, shot through with a deep anxiety about the rise of totalitarianism (not to mention the arrival of the bomb). George Orwell’s 1984 had been published a year earlier, and Hannah Arendt’s Origins of Totalitarianism would appear a year later. What makes Wiener’s work distinctive, and of particular interest today, is his attention to the arrival of powerful new machines of calculation and communication — von Neumann’s digital computers — and the role they might come to play in the unfolding story of politics, power, and social change.

Toward the end of the book, after discussing Claude Shannon’s ideas about the possibility of chess-playing machines, Wiener speculates that computers, as they advance, may come to be relied on for making a wide array of decisions, including governmental ones. Indeed, he suggests, the speed and rationality of computer calculations may eventually give “machines à gouverner” a decisive advantage, if perhaps only an illusory one, when in competition with slow, fallible human decision makers.

Because it would have to operate under conditions of uncertainty, as policy-makers and bureaucrats do, a governing machine would need, Wiener stresses, to be a learning machine, capable of making decisions based on calculations of fluctuating probabilities rather than just following a set of fixed rules. While that requirement makes the challenge of developing such a machine “more complicated, [it] does not render it impossible.” In an unpublished article he had written a few months earlier, Wiener posited that a computer would become capable of learning once it was able to start programming itself in response to its inputs: “The possibility of learning may be built in by allowing the taping [i.e., coding] to be re-established in a new way by the performance of the machine and the external impulses coming into it, rather than having it determined by a closed and rigid setup, to be imposed on the apparatus from the beginning.” He was foreseeing, if only hazily, the development of what we now call generative AI.

Building on that idea in The Human Use of Human Beings, he argues that, once set in motion, machine learning might advance to a point where — “whether for good or evil” — computers could be entrusted with the administration of the state. An artificially intelligent computer would become an all-purpose bureaucracy-in-a-box, rendering civil servants obsolete. Society would be controlled by a “colossal state machine” that would make Hobbes’s Leviathan look like “a pleasant joke.”

What for Wiener in 1950 was a speculative vision, and a “terrifying” one, is today a practical goal for AI-infatuated technocrats like Elon Musk. Musk and his cohort not only foresee an “AI-first” government run by artificial intelligence routines but, having managed to seize political power, are now actively working to establish it. In its current “chainsaw” phase, Musk’s DOGE initiative is attempting to rid the government of as many humans as possible while at the same time hoovering up all available government-controlled data and transferring it into large language models. The intent is to clear a space for the incubation of an actual governing machine. Musk is always on the lookout for vessels for his seeds, and with DOGE he sees an opportunity to incorporate his ambitions and intentions into the very foundations of a new kind of state. It’s preformationism writ large.

If the new machine can be said to have a soul, it’s the one Turing feared: the small, callow soul of its creators.

4.

Even more than a flesh-and-blood bureaucracy, Wiener understood, an inscrutable bureaucracy-in-a-box, issuing decisions and edicts with superhuman speed and certainty, could all too easily be put to totalitarian ends. The box might seem autonomous, its outputs immaculate, but it would always serve its masters. It would always be an instrument of power. “The modern man, and especially the modern American, however much ‘know-how’ he may have, has very little ‘know-what,’” Wiener wrote. “He will accept the superior dexterity of the machine-made decisions without too much inquiry as to the motives and principles behind these.”

To explain his distinction between know-how and know-what, a distinction he saw as critical to the future course of technological progress, he tells another story:

Some years ago, a prominent American engineer bought an expensive player-piano. It became clear after a week or two that this purchase did not correspond to any particular interest in the music played by the piano. It corresponded rather to an overwhelming interest in the piano mechanism. For this gentleman, the player-piano was not a means of producing music, but a means of giving some inventor the chance of showing how skillful he was at overcoming certain difficulties in the production of music. This is an estimable attitude in a second-year high-school student. How estimable it is in one of those on whom the whole cultural future of the country depends, I leave to the reader.

This post is part of Dead Speech, the New Cartographies series on AI and its cultural and economic consequences.

Dyson would reuse the title for his 2012 book, Turing’s Cathedral: The Origins of the Digital Universe.

This reading of Google’s intentions gains credibility when one considers the long, steady decay in the quality of the search engine in the years since — to the point where it now gives precedence in its results to AI slop of dubious reliability.

This article reminded of the Frank Herbert quote, "Once men turned their thinking over to machines in the hope that this would set them free. But that only permitted other men with machines to enslave them."

I love substack because of gems like this. Absolutely fantastic work